Ideas for Side Projects

Ideas

Below are a compilation of both big and small project ideas I have. The ‘big’ ones are the ones that have actual significance and would take a non-trivial amount of effort to pull-off, while the ‘small’ ones are just relatively novel ideas I have. A lot of these have to do with PGAS-related experimentation and center around Chapel, which is an ideal testing ground for these kinds of experiments.

Big Project Ideas

Chapel-MPI (Proxy) [2020-02-24]

Currently, Chapel has an MPI module and low-level C_MPI module, as well as ways to setup MPI to run on MPI across different network stacks (primary GASNet/Infiniband) or interoperate with them (Cray’s GNI/uGNI). Currently, it is possible to treat Chapel as a single-locale process, running as an MPI process, and also a way to intermix Chapel’s locales with MPI ranks. The former is clearly antithetical to Chapel as a whole as you can no longer make use of its excellent data and task parallel constructs, and the latter constrains MPI to a single MPI process (rank) per compute node, severely limiting parallelism for codes that do not make use of Hybrid MPI (OpenMP + MPI).

The problem is that existing MPI libraries assume that they are primarily in control of communication, as does Chapel. Getting them to play ‘nicely’ together requires a compromise that comes at the cost of convenience, productivity, and performance. The solution that I have devised is based on how UPC++ handles interoperability with MPI, in that MPI and Chapel communication must occur at strictly disjoint times, and all communication should be handled by one or the other, but not both. This is necessary to prevent deadlocks where MPI processes perform collectives (all-to-all, reduce, scatter-gather, etc.) and to not conflict with the communications layer. The core problem with this approach in utilizing existing libraries is that they make special assumptions and lay invariants that we need to violate.

In particular, the Chapel-MPI library would be more of a proxy library, or a shim, that could basically forward to a modified version of an existing MPI library, or even translates them into a way that Chapel’s communication layer can process. Another idea is to modify an existing MPI library and bundle that with Chapel, and to have it create pinned threads and destroy them on-the-fly as necessary, while treating them as MPI processes, ensuring parallelism. The idea that I am the most excited about is the following…

Modification of Existing MPI library

- When an annotated function that performs an MPI call is to be performed, jump from Chapel to MPI mode…

- Given

MPI_RANKSandMPI_NODES, which should map to existing locales (compute nodes) and threads (ranks). These locales and threads act as proxy MPI ranks. - In the tasking layer, create a non-yielding task and barrier until they all finish (without yielding to task scheduler)

- In the communication layer, wait for all existing communication to finish (Chandy-Lamport)

- Enter MPI function: MPI communication proceed as expected, utilizing the existing MPI library calls.

- Exit MPI function: Terminate non-yielding tasks, communication is now free to continue in Chapel

GPU Kernel Generation via Symbolic Execution [2020-02-24]

Currently, Chapel, despite having multiple collaborative attempts to adding native GPU support, one from Nvidia and another from AMD, and some attempts at promoting productivity towards the integration of GPU kernels with Chapel such as GPUIterator, there has not been an approach towards generating GPU kernels from inside of Chapel. I started the idea for such work by taking a python-like approach of creating wrappers that act as symbolic variables, which overload operators and record any and all operations performed on said symbolic variables, generating an abstract syntax tree that can then be analyzed and optimized into a GPU kernel that could be run on the GPU. Example code could be seen below…

Example Code written by User

var x = kernel.createScalar("x", GPUVariableType.INT);

var arr = kernel.createArray("arr", GPUVariableType.INT, 10);

for a in arr {

a += 1;

x += a;

}

Which will generate…

int x;

int arr__size;

arr_size = 10;

int *arr = malloc(sizeof(int) * arr__size);

for (int __idx__ = 0; __idx__ < arr__size; __idx__++) {

arr[__idx__] += 1;

x += arr[__idx__];

}

This isn’t too far off from what a GPU kernel could look like, and is merely a proof-of-concept. The output of a optimized GPU kernel could possibly be not too far off. The motivation behind this is to allow users to write high-level GPU kernels using Chapel’s syntax and semantics, and have it be translated into a compliant GPU kernel.

Amortized Time Complexity Profiler [2020-02-24]

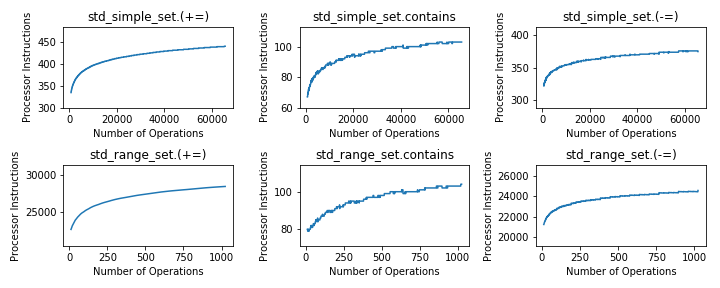

Proof of concept can be seen here. By using performance counters, it is possible to test complexity by graphing the number of instructions executed to the number of operations. This has been rather successful in determining the amortized complexity, and was used in a homework assignment where the students had to ensure time complexity matched the specification.

The goal is to perform image classification to automatically classify these curves as a specific complexity (logarithmic, quasi-linear, linear, constant, quadratic, cubic, etc.); more useful would be to perform some kind of linear regression to obtain an actual useful upper-bound equation for time complexity, I.E maybe something as precise as O(N^2 + N log (N) + N + C) instead of just O(N^2), perhaps by obtaining a line that best fits the line with the least number of dimensions (for example, dimension 0 is C, dimension 1 is log(N), dimension 2 is N, etc.) This could be very useful as a profiling tool and for proving time complexity of algorithms where it actually matters. “Oh, no wonder my code is so slow, it has a time complexity of O(N! + 2^N)!”

The main barrier for this project is the math required, and that my experience with machine learning is relatively limited, and my experience with performing advanced linear regression to this extent (I.E I need novel information that normal models cannot provide, requiring a mastery… or maybe I’m so inexperienced that I don’t even know its easier to do than I think…) I have asked others, one data scientist (a professor of a class I took) and an HPC expert (a DoE CSGF Alumni) and both pretty much recommend I limit the scope of the project… but I want to push the boundary and make something cool, and this would be the coolest contribution I could make, I believe.

Small Project Ideas

Distributed Barrier [2018-08-22]

While glossing over a paper called “Barrier Synchronization: Simplified, Generalized, and Solved without Mutual Exclusion”, it gave me an idea for how this can be implemented in Chapel. First, I’ll go over the idea proposed in the original paper and then make my own adaptations and improvements on it.

In this paper the author, Alex Aravind, presents a Ring Barrier implementation where each processing unit, p, out of N, which I will denote as p{i}, for i in [1..N], will notify its neighbor when it is notified by its predecessor. Hence p{i} notifies p{i+1} and gets notified by p{i-1}. The key point here is that while p{i} is awaiting notification, it will be spinning locally, and when it needs to notify a neighbor it can do so using only a single remote memory access. After the p{i} has notified its neighbor, it will then wait on a flag that may or may not be remote. Below is a basic sketch of the algorithm in Chapel.

// Number of tasks that must hit barrier

const numTasks : int;

var epoch : atomic int;

var tids : atomic int;

var tid = tids.fetchAdd(1) % numTasks;

var signal = epoch.read(memory_order_relaxed);

var status : [0..#numTasks] atomic bool;

// If we have task id #0, we are bootstrap the process

if tid == 0 {

status[tid + 1].write(signal);

status[0].waitFor(signal);

} else if tid < status.domain.high {

status[tid].waitFor(signal);

status[tid + 1].write(signal);

status[0].waitFor(signal);

} else {

status[tid].waitFor(signal);

status[0].write(signal);

}

// Update epoch; ensures it is only incremented once per pass

epoch.compareExchange(signal, signal + 1);

Unlike in the paper, Chapel does not provide thread-local storage or task-local storage yet, and so each task must acquire their own ‘tid’ from the atomic counter tids. As well, the current epoch must be read which is used as the signal to wait on and to send to neighbors as they wake up. After waiting on the signal, each task will perform a compare-and-swap to swing the epoch forward one, and since it is compared to what was read from the epoch it will only be swung forward once.

TODO: Distributed Version

Distributed Reader-Write Lock [2018-01-21]

TODO:

Overall idea:

- Have one global write lock

- Have task-local/thread-local reader-writer locks to reduce contention

- Writers must acquire global write lock and each task-local/thread-local reader-writer lock for each node.

- Readers only acquire task-local/thread-local reader-writer lock

Benefits: Readers are uncontended when they acquire the reader-writer lock for majority of time, and even when they are they do not require any communication, either between nodes or other threads. Drawbacks: Writers are super-slow, similar to RCU except that they require actual mutual exclusion from concurrent readers, but are simpler in that memory reclamation is made easy. Should have comparable performacne when writes are seldom.

Distributed Vector [2018-01-08]

TODO:

Overall idea:

- Make use of wait-free atomic fetch-and-add counters; useful for performing obstruction-free helper-bounds-checking, and for maintaining consensus over the global head and tail.

- Have one concurrent linked list per core per locale and store the head/tail count in each node and sort by said count. Tasks only takes node if their fetch-add count matches

Benefits:

-

By using the helper bounds-checking algorithm, we ensure that communication is only interrupted when a task attempts to add an item when the data structure is full, or attempts to take an item when the data structure is empty. This scales extremely well so long as the user is conscious about their usage.

-

By keeping a Fetch-and-Add counter for the head and tail, we ensure that claiming a position is entirely wait-free in both computation and communication. This scales phenomanally, especially if the head and tail counters are allocated on separate nodes to prevent any one node from getting ‘bogged down’.

-

By keeping a concurrent linked list per core, we can ensure that if there is a remote ‘executeOn’ statement, we can ensure that we have at most maxTaskPar tasks performing an operation at any given time while gaining concurrency. By doing this for each node it is distributed over, we gain more parallelism/concurrency as we increase the nodes we distribute over.

-

By keeping the concurrent linked list sorted we allow readers to scan the list for their operation. By keeping the read head/tail count in each node, we ensure that if a task successfully performs a fetch-and-add on the head/tail without yet adding their element to the list does not cause another task to remove another node out-of-order. This ensures we maintain an overall order on the data structure.

-

Can make use of Cray Aries NIC hardware ‘Network Atomics’.

Drawbacks:

- Relies on Quiescent State-Based Reclamation and a concurrent sorted linked list.

- Relies on network atomics for true scalability.